The dangers of printing money are well-documented. Too much money chasing too few goods leads to higher prices and lower growth.

Hundreds of billions of pounds of so-called

quantitative easing

(QE) during the financial crisis skewed this perception as the Bank of England repeatedly fired up the printing presses to try to revive the UK’s ailing economy.

Inflation at first failed to rear its ugly head, until it did. And policymakers and taxpayers are now counting the cost of Britain’s £895bn monetary experiment.

QE is a process where Threadneedle Street creates money that is used to buy government bonds, known as gilts, to help drive down the cost of borrowing.

Commercial lenders then park that cash at the central bank where they earn interest at the current base rate.

When interest rates were at record lows of 0.1pc during the pandemic, the Bank earned far more on the returns from government bonds than it had to dish out in interest.

By the end of 2021, the Old Lady was in profit to the tune of £123.9bn.

But that was quickly eroded when interest rates started rising, with a “consistently higher Bank Rate” resulting in “large interest losses” of £18.5bn in the last financial year alone, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

But that’s not all. The Bank is also actively selling its stockpile of gilts back to the market in a move called quantitative tightening (QT), crystallising billions of pounds of losses for the taxpayer .

Many economists, politicians and central bankers believe this is a mistake, as it means that some of the bonds Threadneedle Street bought during the crisis are being sold at knockdown prices.

In some of the most extreme cases, bonds bought for the equivalent of £1 have been sold for 28p.

These so-called “valuation losses” will dwarf the money being paid out in interest if the Bank continues to actively reduce its stockpile of gilts by around £48bn a year.

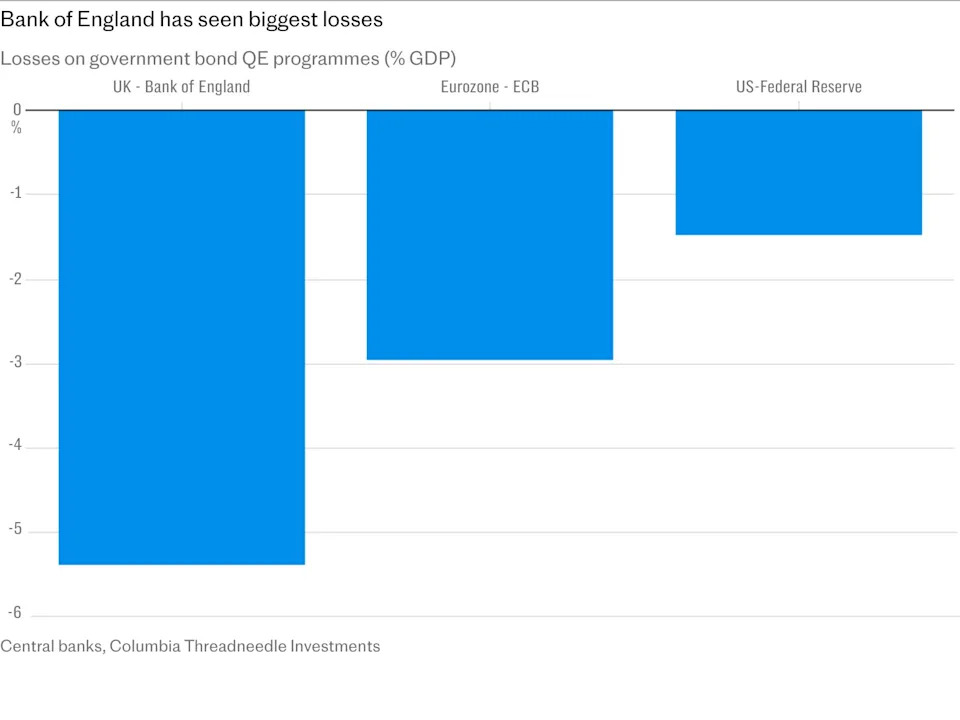

The total cost to the taxpayer over the scheme’s lifetime is currently estimated at around £150bn by both the Bank of England and OBR. That’s the equivalent of a £5,000 tax on each household.

QE was never intended to be permanent, but few predicted it would turn out to be so expensive.

When Labour chancellor Alistair Darling first authorised the so-called

asset purchase facility

(APF) to hoover up £50bn of bonds in January 2009, he assured the public that the assets would be “held for no longer than is necessary to ensure stability and protect taxpayer interests”.

However, more than 15 years after the first tranche of money printing was put into action, the amount of gilts held in the Bank’s asset purchase facility remains at £620bn.

Lord King, governor of the Bank at the time, says policymakers have reached for the QE tool too readily.

Speaking at an event last week, he said: “I think what that led to was a view that 2016 ... [became], I’ve got some bad news here, we’ve voted to leave the EU. If we get bad news, we’ve got to do something; let’s do QE. Pandemic: bad news again, what do we do? Let’s do QE.

“But there are some kinds of bad news that do require a monetary policy response and other kinds of bad news that do not justify a monetary response.

“You’ve got to be able to tell the difference between the two. I think the QE in 2020 went way beyond stabilising markets without any plausible justification for it.”

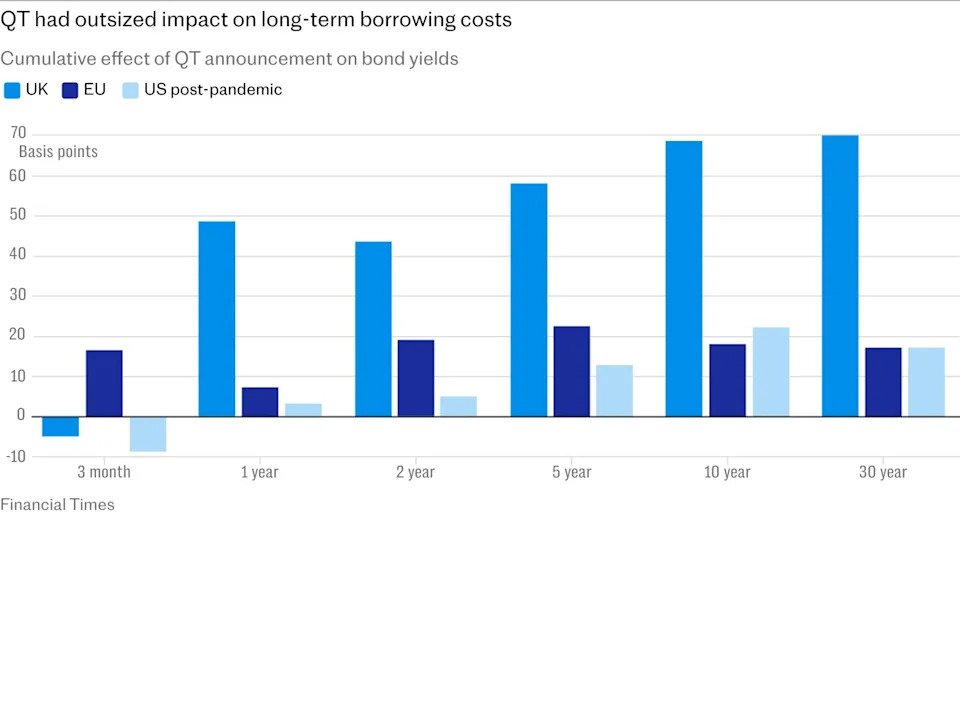

Research published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) last year blamed active QT, where the Bank sells bonds back to the market before they mature, for raising Britain’s long-term borrowing costs by around 0.7 percentage points.

Sir John Redwood, a former director of policy for Margaret Thatcher, says the damaging costs of QT are unlikely to prevent similarly bad choices from being made in the future.

“I don’t think the authorities learnt anything from this disastrous experiment that is having such a big impact on the public finances,” he says. “It is self-inflicted harm on a huge scale.”

“The Bank of England has provided no cogent justification for selling bonds for big losses in the market. It says it doesn’t have a monetary impact. Well, that is wrong [and] no Chancellor has challenged it.”

There is a general sense that politicians are starting to wake up to the issue.

Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor, wrote to Andrew Bailey last week in a letter that impressed on the Governor three times that the process of reducing the Bank’s stockpile of bonds must provide “value for money”.

The Bank’s decision to delay an

auction of long-term debt

after Donald Trump sparked bond market jitters with his tariff tirade shows that it’s listening, while the Treasury’s Debt Management Office is also moving away from long-term debt.

There is another big shift happening in the background that will, with any luck, help the Bank leave behind its radical money printing era. Instead of buying bonds, the central bank wants to move to a more normalised system of providing cash on demand through what’s known as repurchase or “repo” operations.

Paul Tucker, a former Bank deputy governor, says it’s time to move away from a reliance on QE to fix crises.

“I think in this country, the Bank has lost the sense of a distinction between a market maker of last resort intervention, where you purchase government bonds, and a QE intervention, where you’re purchasing government bonds to stimulate aggregate demand,” he says.

“The bank has, since the liability-driven investment (LDI) episode, gotten closer to what I think should be orthodoxy.”

Orthodoxy means actually sticking to the late Darling’s principle of temporary and targeted intervention.

It turns out that targeted intervention can be quite profitable for the taxpayer. The Bank made £3.5bn by buying almost £19.3bn of long-term government debt following the LDI crisis that threatened pension funds in 2022.

Meanwhile, it comes as politicians across the spectrum are paying greater levels of attention to the process of quantitative tightening.

Reform has vowed to stop paying interest on reserves held at the central bank in a move it claims could save £35bn a year.

However, Bailey warned in a recent speech that this could undermine the Bank’s task of keeping inflation low “and could cause significant harm to the credibility of monetary policy”. In other words, the Bank could lose control.

Bailey has also highlighted that moving back to a world where the Bank responds to demand rather than actively buying gilts could make taxpayers more cash.

Threadneedle Street takes a small cut every time commercial banks tap the Bank for cash and that money can quickly add up.

Sanjay Raja, at Deutsche Bank, says there is a case for winding down the Bank’s stockpile of gilts entirely.

“This would, ultimately, reduce the Treasury’s transfer payments to the Bank, and reduce the fiscal burden of its QE operations,” he says.

Raja also believes the bar for future QE is already higher.

“The effects of QE have been mixed,” he says. “Concerns on taxpayer value for money have also now come to the fore.

“And given the political attention that QE and QT have attracted, central bankers may be more wary of turning to QE in the first instance – unless, of course, the occasion calls for it.”

But don’t wave goodbye to QE just yet. One former insider says that while the Old Lady may be scarred by money printing, that doesn’t mean she won’t fire up the printing presses again.

“I can tell you that the government of the day were desperate for us to do whatever we could,” they recall. “They wanted to go much further, much faster, buy all sorts of stuff, and whatever it took to rescue the economy”.

So if desperate times fall again, QE may be the Bank’s only option – regardless of how much pain it will cause the taxpayer for decades to come.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.